Judex Ergo Sum

|

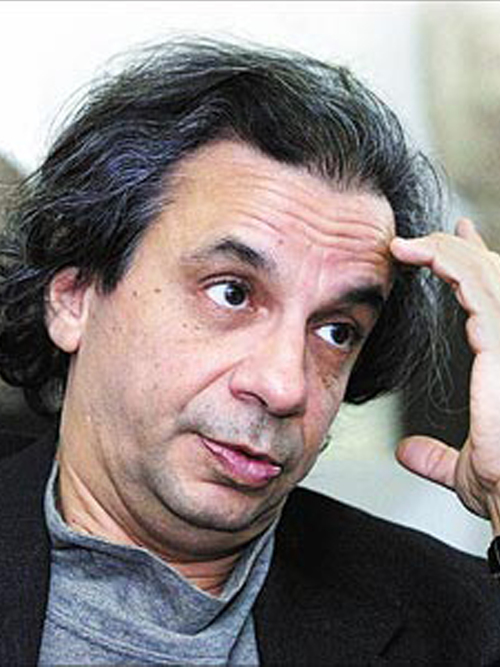

| Akeel Bilgrami |

Akeel Bilgrami, in his recent essay attempting to unpack Gandhi's views on caste, frames the approach as one grounded in a view of the pre-modern, pre-capitalist society as distinctly different from viewing the members of society as merely constituents of an economy. This, he argues is the key to understanding the evolution of Gandhi's stance on caste.

This instructive essay is, in some ways, an elaboration of his interview to Frontline in 2018, where he mused on the tension inherent in the slogan: Liberté, égalité and fraternité, and the points at which the Marxian and Gandhian outlook towards this tension, overlap and distinctly depart from one another.

The crux of Gandhi's conundrum that folks across the political spectrum can relate to is what Bilgrami succinctly states thus:

to retain caste was to resist the market ideal that undermined traditional social relations by setting up the freely saleable labour of atomised individuals.

This sympathy of Gandhi was unsurprisingly rejected as a bad-faith defence of the status-quo, by Ambedkar.

|

There were a few parts of the essay that provoked me into visiting my biases - always an unpleasant exercise - which in turn provoked me to write this meandering post and foist it on you.

For instance, Bilgrami writes:

Gandhi, as a social philosopher writing on caste, is invoking a conjectural past in a theoretical deployment of mythos with the same theoretical motivation as a much more modernist mythos is invoked by any number of political philosophers, who appeal to a conjectural past when they, for example, posit a social contract.

Now, I perfectly perfectly understand and appreciate what Bilgrami is trying to do here.

A 'modern' mind (like that of Ambedkar) would have little patience for Gandhian conjectures about the origins of our caste system being horizontal and the hollow assertion that hierarchy was only a latter day corruption.

Snidey segue

By the way, such humorous conjectures are popular even in Hindutva circles (varna is about guna not birth) and Tamil Desiyam circles (Sangam kudis were osmotic). I conclude that is because most folks are unable to summon the gumption to see the obvious ('I hold this truth to be self-evident'!): birth based hierarchy/assignment of roles IS civilisation itself.

Cultural-political formations need their consolatory fictions to stitch together folks across the board against an 'other'; so they appeal to some sense of common pride (ethnocultural, linguistic, religious). They need to do that while ignoring the unseemly, yet essential, systemic rigours that enabled the civilisation itself. That is all there is to any claims that any time in the past was ever more 'equal' than a future we all trundle to.

Conjecture as a device of illumination

Bilgrami is attempting to stave off the reflexive rejection that a modern mind is wont to reach for, when faced with the Gandhian conjecture of, 'caste as horizontal diversity', and thus allow us to dwell on the approach sufficiently long.

Lenin's critique of the Narodniks, that Bilgrami elaborates on later in the essay, is especially enlightening to better understand Gandhi's sympathies and limitations.

|

| Ayothidasa Pandithar |

Now, would I be as willing to extend the same courtesy to the conjectured alt-histories of, say, Ayōthidāsar?

Most certainly not!

Try as I might (and the Lord God knows I have tried again and again) I end up being annoyed at how his conjectures are largely baseless and highly motivated. I resent the recent ascendancy his far-fetched theories are having in the political mainstream.

Snidey Segue 2

Reminds me of Rāma telling Vāli (you see, I am maxing out on delusions of grandeur, but hey it's my blog!) that he knew enough about proper-conduct to excuse himself by circumstances of location. He says:

| The saint: Gee, wassup doc? |

நின்ற நல் நெறி, நீ அறியா நெறி

ஒன்றும் இன்மை, உன் வாய்மை உணர்த்துமால்

You know that which is right

There is nothing about rightness that you know not

Your words themselves stand testament.

(And yet you feign ignorance and advance fallacious arguments)

Appeal to Authority

In his response to Ambedkar's 'Annihilation..', Gandhi wrote several articles in his paper 'Harijan' (that have been collated here under the heading 'A Vindication of Caste'). A telling line in that is

Nothing can be accepted as the word of God which cannot be tested by reason or be capable of being spiritually experienced.

This typically Gandhi; emotive slipperiness, as opposed to Ambedkar's usually rigorous logic.

Many have criticised Gandhi as being intentionally sloppy, making an oily attempt to appropriate the chair of critic, assuming the language of inquiry but in the end, protecting the status-quo from the debilitating assault of rationality.

Ambedkar responded immediately and sharply (covered earlier here). He rightly accused Gandhi of not daring to imagine boldly enough to bring down moribund structures.

|

| Who can I presume to advice a magician? |

Although Nehru had his typical modern distance - even disdain - for much of what traditions stood for, it would be fair to say, that he spoke from a luxury that came from taking for granted the second order effects of the culture, enabled by sheer survival.

On the other hand, the conservatives would be fair to ask 'Who is Gandhi to filter and mould what constitutes tradition?'

The disgruntlement was best articulated by God himself in Job 40:8

“Would you discredit my justice?

Would you condemn me to justify yourself?

But, pragmatically speaking, the conservatives today would do well to see the selfsame question proceeds from those who would have traditions tabula rasa'd by the eventuality that is 'modernity'.

For those conservatives who find the the spectrum of postures on offer : from humanist bleeding heart sympathy to the studied nonchalance in the face of eventuality - to be unappetisingly limited, this realisation should give some pause.

In his 1966 essay Chakravathi Rajagopalachari and Indian Conservatism, Howard L.Erdman writes:

That there may be a latent communalism in Rajaji's approach cannot be doubted. That it will not become overtly communal in Rajaji's hands is, perhaps is one of the best things that can be said about his conservatism, but it is my no means insignificant

Anyone with a cursory familiarity with Rajaji's writings and works would find this summary quite harsh and uncharitable.

There is no such statesman today who considers it his duty in history to moderate the tide of change. Polity is so polarised that we only have a justification of untrammelled individual agency and its consequent reactionary stifling.

Whose Call

Which brings this meandering blogpost to the point of permanent interest of this blog: me.

I am forced to face the utterly subjective and highly biased nature of my choices on what kind of conjectures I indulge insofar as they promise some edification, and what kind of conjectures I dismiss as mischievous, tainted by unscrupulous intent and portend a terminal upending of narratological propriety.

|

| Lenin debates Mikhalovsky - by Boris Lebednev |

why are the actions of some living individuals called elemental, while of the actions of others it is said that they “move events” towards previously set aims? It is obvious that to search for any theoretical meaning here would be an almost hopeless undertaking. The fact of the matter is that the historical conditions which provided our subjectivists with material for the “theory” consisted (as they still consist) of antagonistic relations and gave rise to the expropriation of the producer. Unable to understand these antagonistic relations, unable to find in these latter the social elements with which the “solitary individuals” could join forces, the subjectivists confined themselves to concocting theories which consoled the “solitary” individuals with the statement that history is made by “living individuals.” The famous “subjective method in sociology” expresses nothing, absolutely nothing, but good intentions and bad understanding.

Ouch!

The likes of Ambedkar would not accord even that 'good intention but bad understanding' characterisation to guardians like Mahatma Gandhi.

Code

| G.K.Chesterton |

When conscience and morality are informed by a code, how does one presume to decide what is a benign - or rather even necessary - mutation of the code?

As Chesterton said (as only Chesterton can)

“We do not want a church that will move with the world. We want a church that will move the world.”

A conservative reading this and nodding his head in agreement, would find himself in curious agreement with Lenin's above critique of Narodnik's sociology (and by a similar token Ambedkar's criticism of Gandhi) - except that the conservative operates from the completely opposite sympathies. He wants to - well duh! - conserve.

Perhaps, a conservative's curiosities would lie in knowing what tradition has to say about change and the 'great individuals'.

Elemental is not elementary

Rāmā is praised as the embodiment of dharmā itself. Kamban refers to him as அறத்தின் நாயகன், தருமமூர்த்தி and such.

And yet he is not the great individual who deviates and lords over change. But he is the figure who adheres and upholds the code. In Mikhailovsky's words 'elemental'. Now this is not a sacrilege to be apologetic about, because in the Sanātana tradition, to be called 'elemental' is hardly a derisive epithet but is actually fulsome praise.

For instance when rebuffing the advances of Sūrpanaka, the words he uses to rebuff it not because he was married but that he was a Kshatriya and she was of Brahmin descent and it would be inappropriate (pratilōma) union:

அந்தணர் பாவை நீ; யான் அரசரில் வந்தேன்' என்றான்

Tolkāppiyam explains an appropriate union thus:

ஒத்த கிழவனும் கிழத்தியும் காண்ப

மிக்கோ னாயினும் கடிவரை யின்றே

The 'equal' hero and heroine shall meet

If the hero is her better that is also acceptable

If I may paraphrase what the principal grammarian says: even when depicting a love-at-first-sight situation, the poet had better ensure it is NOT a pratilōmā

And pray what are measures of 'equality'? Tolkāppiyar clarifies in the very next verse

பிறப்பே குடிமை ஆண்மை ஆண்டொடு

உருவு நிறுத்த காம வாயில்

நிறையே அருளே உணர்வொடு திருஎன

முறையுறக் கிளந்த ஒப்பினது வகையே

The ten points of comparison (to determine equality are)

Birth, Clan, Ability, Age

Beauty, Love

Propriety, Grace, Feeling, Wealth

Now, Tolkāppiyam's poruL-athikāram is a style-guide governing ideal depictions in poetry. While it is not a smriti that dictates social relations of its age (whenever that was!), insofar as it suggests the depictions palatable to the audience, it can be understood to be reflecting the social morés of its day.

This poses an obvious problem to those whose entire sociopolitical identity is steeped in the fictive Tamil exceptionalism, which rests on the uneasy (and absurdly untenable) assumption of an 'equal' past. So, all these inconvenient verses have been handled using the highly predictable cope of branding them en-masse as 'wily latter day interpolation'.

Man, in his element

So, much like when justifying his felling of Vāli as one consistent with the code, in this rebuffing of Sūrpanakā, Rāmā clearly says he is adhering to the code (as explained quite accessibly in the verses in Tolkāppiyam above).

On, the other hand, Dushyantha (father of the eponymous Bharatha) dealt with the conflict between adherence to a code and a supposed deviation, quite interestingly.

He finds himself drawn to Sakuntalā - who is ostensibly a muni kanyā.

Now can he wed her in a gandharva vivāha - a union decided just by the consent of the man and woman in question.

A Kshatriya man ought not to marry a Brahmin woman.

And secondly, gandharva vivāha was not permissible for Brahmin women

Periyāzhwar - one of the few Brahmin Azhwārs in the Tamil Vaishnavite tradition, assuming the tone of the mother grieving on behalf of her love-lorn daughter (a beautiful Sangam Tamil trope, seamlessly ported into Bhakthi literature) sings:

வேடர் மறக்குலம் போலே

வேண்டிற்றுச் செய்து என்மகளைக்

கூடிய கூட்டமே யாகக்

கொண்டு குடி வாழுங் கொல்லோ?

நாடும் நகரும் அறிய

நல்லது ஓர் கண்ணாலம் செய்து

சாடு இறப் பாய்ந்த பெருமான்

தக்கவா கைப்பற்றுங் கொல்லோ?

Will the Lord who vanquished Sakatāsura

Properly take my daughter's hand

In a manner that town and country know

Or will they just cohabit

And consider that marriage enough

As is done amongst hunters and Kings

|

| Gandharva couple : Chandela sculpture |

Now, as discussed earlier, even such a union ought not to be pratilõma (where the கிழவன் is neither ஒத்த nor மிக்கோன் of the கிழத்தி).

But, Dushyanta reasons that, given his hitherto unflinching adherence to the code, his conscience is a reliable moral compass and he would not have been drawn to something violative of the code.

He gives himself a compliment that 'when in doubt, the instinct of good-men is a reliable guide to truth'

|

| Translated by Monier Williams |

The literalists who infer from this a mere justification for perpetuation of inequities, are best left to converse among theirs peers.

But for those who can abstract away atleast to the level of the Lenin-Mikhailovsky debate, this circular reasoning would be quite striking.

For instance, I shall invite you to muse on how the mixed varna lineages as listed in famous tenth chapter of Manu do not exactly map to the what is mentioned in the Anushasana Parva of Mahabharatha.

Does it not beg the questions:

-how many non-elemental, 'great individuals' were there to effect the changes to re-codify this?

-What were the intervening changes that disturbed the stasis to urge the recording of the re-codification? - - What extent of technological stasis and demographical insularity/stability would have enabled a relative cultural continuity before the next civilisational perturbance?

Now, how this ties into Gandhi's views on caste, technology, trusteeship economics, Hindi Swaraj, Harijan welfare, village self-reliance, decentralisation, Hindu-Muslim relations and so on, is left as an exercise for you, my dear reader!

Ref:

- Akeel Bilgrami 2023, Gandhi and Liberal Modernity: The Vexed Question of Caste

- Akeel Bilgrami 2018, Interview to Frontline Gandhi, Marx, and the ideal of an 'unalienated life

- This blog, எட்மண்ட் பர்க்க்

- Mahatma Gandhi, A vindication of Caste

- Howard Erdman 1966, Chakravathi Rajagopalachari and Indian Conservatism

- The Laws of Manu (translated by George Bühler) - Chapter X

- The Mahabharata (translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguly) - Anushasanika Parva SECTION XLVIII

- Rāmā's response to Sūrpanakā - ஆரண்ய காண்டம் கோவை கம்பன் ட்ரஸ்ட் உரை

- Rāmā's response to Vāli - கிட்கிந்தா காண்டம் கோவை கம்பன் ட்ரஸ்ட் உரை

- Boris Lebedev s painting The Dispute Between Lenin and Narodnik Mikhailovsky From the Lenin s Youth series

- பெரியாழ்வார் திருமொழி 3.8.6

- Gandharva Couple pic

- Abijnāna Sakuntalam - translated by Monier Williams

Comments

Post a Comment