Rules and Rulers

In the original story of Sakuntala, as told in the Mahabhratha, there is no ring.

Sakuntala appears in Dushmanta's court with their son and requests Dushmanta to declare him the heir to his throne, as he had promised her, before their gandharva vivāham.

Though Dushmanta very much remembers their encounter (and thus recognises legitimacy of the claim), he still pretends not to remember and asks her provocative, insulting questions in his court.

But he is 'being cruel only to be kind'. For, this sets the dramatic stage for a fine articulation of her case by Sakuntala, which ends in the divine voice from the sky, declaring her to be true and for Dushmanta to accept her and their son.

Dushmanta Feigns

I am given to understand, by the Sanskrit literate, that the expression smaraNN api , is the clincher here. It means Dushmanta DOES remember and yet chooses to be harsh to Sakuntala to provoke her to make her case in open court. And boy she does: she marshals what the scriptures have to say about the honour of a wife, the one who provides the lineage, and thus the one who ensures the ancestors are provided for, via the ritual observances.

Mind you, this whole story is narrated by Vaisampāyanā to Janaméjaya. So, Janaméjaya is thus hearing about the ideals of marital partnership and wifehood from the mother of his illustrious ancestor Bharatha himself.

That she focuses on this aspect of the wife (jāyā - the one who brings forth) than the other aspects (like patni - the one who is a partner in a sacrifice) is one example of her precision.

அஶரீரி

And just as she turns her heels and walks away from court, the heavenly voice declares her claims to be legitimate

And then Dushmanta explains to his courtiers that he had intentionally directed proceedings in this manner so as to scorch any trace of doubt.

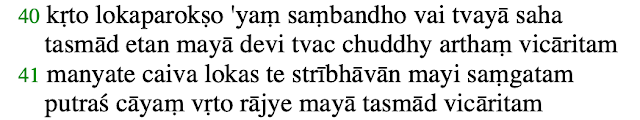

After having told this to his courtiers, he then further explains to Sakuntala why he had to put her through the grind:

Unapologetic Forgiveness

He does NOT feel apologetic at all that he has put caused his beloved considerable anxiety, been unduly harsh to her. In his mind, this was needed in the pursuit of dharmā. Of course, since Sakuntala was not aware of his motivations, her un-wife like harsh words are understandable and can be gracefully forgiven!

This absolutely stunning moment, is what seems to separate Vālmiki's Rāma and Vyāsa's Yudhishtra.

The former seems clear in his commitment. Whereas Yudhistra is perpetually vacillating between striving to conform to dharmā and the pain that his pursuit puts his loved ones through. (Earlier blogged here).

When the AgniParikshai is over and (similar to the Sakuntala story) Brahma declares the purity of Sītā and asks Rāma to accept her, Rāmā says:

|

Kamban and Vālmiki

Note, how - while still reserving high praise for her action - he does not find it out of place to insist 'having to prove herself' was necessary and not unheard of (given her station as the future queen of Ayōdhyā, one infers).

But the tone is still one of appeal - an appeal to his daughter-in-law to understand of his darling son.

Whereas in Vālmiki, he addresses her tenderly but even more firmly thus:

Make no mistake. He is all praise for her action (in the previous verse). But there is difference between 'please do not take it to heart' (மனத்து அடையேல்) and the paternal advice, which is nearly an admonishment: 'thou shalt not render wrath'

|

| Dasaratha with Rāma on his lap - 17th centuryMéwar Rāmāyana paintings |

Lead for செய்யுள்

As I age, it is becoming nearly impossible to not see the friction between the individual instinct and the adherence to codes of conduct in almost everything. After all, the itihāsās were all about giving fullest aesthetic expression to these conundrums to us laity.

Rama chose Ayodhya

— dagalti (@dagalti) September 9, 2022

Love's Sorrow was his own

Edward chose Mrs. Simpson

So Albert got the throne

It seems to bother none now

But I gotta pick a bone

With how Charles chose Camilla

But also got the throne

As time marches on, leaving me and my unrelatable antiquated notions in the dust, a dull anxiety that seems to persistently gnaw is the erosion of sympathies that folks may have towards almost every moment of art I regard as a high-point.

What moved me may likely just cause most now to just shrug!

So, here I mope:

To Do

வகை: கலித்துறை

பதம் பிரித்து

"தீபுகுதீ!" எனும் ராகவர் ஆணையை பூமகளாள் பணிய

தீபுகு தீ சுட தீயினை தீ விட வானவரும் புகழ

தீபுகு தீமையிலாள் அவள் மேன்மையை யாவரும் அன்று அறிய

"தீபுகுதீ!" என கூறி கோ வலி யாரும் அறிந்திலரே

உரை

"தீபுகுதீ!" எனும் ராகவர் ஆணையை பூமகளாள் பணிய

தீக்குள் புகுவாயாக எனும் ராகவரின் ஆணையை பூமகள் பணிய

As the lady of the earth, obeyed the injunction of the Raghava: to enter the fire

தீபுகு தீ சுட தீயினை தீ விட வானவரும் புகழ

தீக்குள் புகுந்த கற்புத்தீயே உருவானாவளான சீதையின் கற்புத்தீயின் வெம்மை சுட, அதைத் தாளாது, அக்நிதேவன் தீயை விட்டு வெளியேற, அவளது செயலை வானவரும் கண்டு புகழ

Her fiery chastity was too hot for the Fire-God himself to handle and he escaped the fire; her act earned encomiums from the celestials

தீபுகு தீமையிலாள் அவள் மேன்மையை யாவரும் அன்று அறிய

"தீபுகுதீ!" என கூறி கோ வலி யாரும் அறிந்திலரே

References

- Mahabharatha : Api Parva - M.N.Dutt's verse-by-verse translation: Chapter LXXIV

- Valmiki Ramayana - Yuddha Kandam, Rama's acceptance of Sita

- Valmiki Ramayana -Yuddha Kandam, Dasaratha's advice

- Kambaramayam - Darasaratha's advice

- Agnipariksha painting - The Mewar Ramayana

- Arthur MacDonnel's comment on the word jāyā

Comments

Post a Comment